The Tolkienic Song of Ice and Fire, Episode II

Bluetiger presents The Wayward Moons of Planetos and Arda

***

Table of Contents

Click on the link – the headline – of the chapter you would like to read or revisit, or scroll down to reach the Introduction and Part I of the second episode of Tolkienic Song of Ice and Fire. Sections which are marked with * are optional – but I encourage you to read them if you have the time, as whilst not directly relevant to the ASOIAF discussion in this essay, they provide context for events, concepts and characters of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Legendarium.

Introduction

The Mythical Astronomy of Ice and Fire by LML: A Summary by Archmaester Aemma

George R.R. Martin and Tolkien

Part I: The Cosmology of Arda

Unreliable Chroniclers, History versus Myth, the Round World and the Flat

The Cuivienyarna*

Tolkienic Caveat

Valar Morghulis

The Valar

Ainulindalë*

Ainulindalë: A Summary by Archmaester Aemma

Lords and Queens of the Valar

The Maiar

The Valar and the Seven

The Two Lamps of the Valar and the Spring of Arda*

The Two Trees of Valinor

The Stars and Constellations of Arda*

Orion: The Swordsman of the Sky

The Stars and Constellations of Arda Continued*

Morningstar before Earendil?*

GRRM and Tolkienic Symbolism

The Elves*

The Chronology of Arda*

The Teleri*

The Noldor and the Darkening of Valinor

The Long Night

The Sun and the Moon

Part II: The Family of Ice and Fire

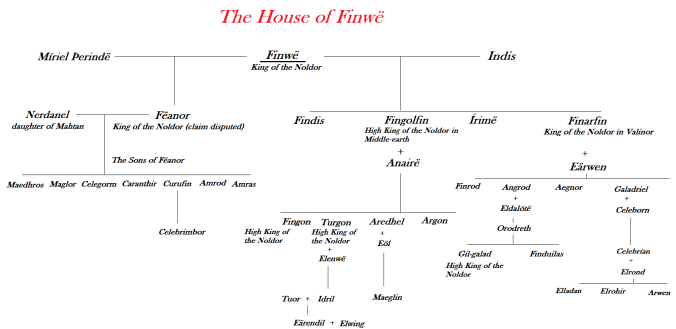

Fëanor: House of Fire

Fingolfin: House of Ice

The Battles of Beleriand*

Fingolfin and his Children

Maeglin and the Fall of Gondolin*

House of Finarfin*

Gil-galad was an Elven-king…

Part III: The Song of the Sun and the Moon

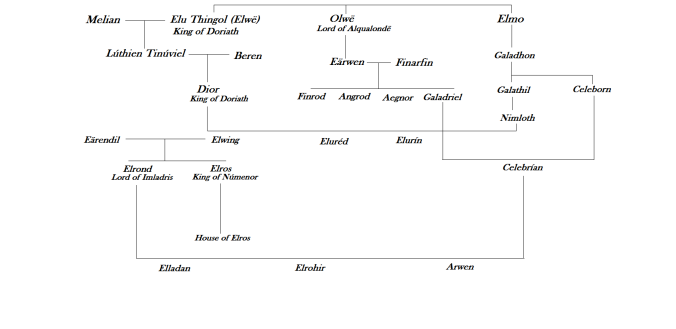

House of Thingol, Elwing*

The Voyage of Eärendil and Elwing to Valinor

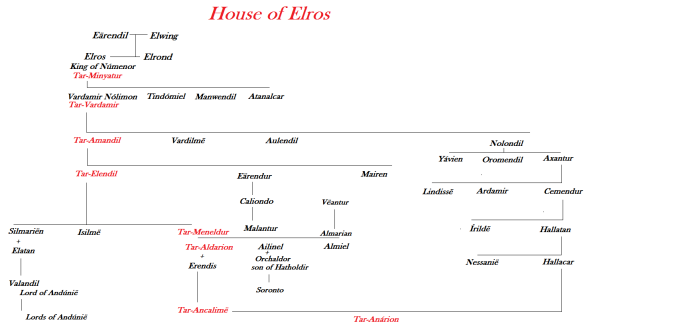

The Dúnedain

The Glory and Downfall of Númenórë

The Unity of the Sun and the Moon

The South: Gondor

The North: Arnor

Minas Ithil, Minar Morgul

Bibliography

***

Introduction

Before I came across LML’s Mythical Astronomy essays I cared little about astronomy, my knowledge was scant at best, and probably even worse, and I saw no reason to become acquainted with this vast field of science. And symbolism based on the observation of the ‘vault of heavens’, changes in the length of day and night, falling stars, constellations and their creation myths, and so on… I saw no use to it. To any symbolism, to be honest. That was something to be discussed during literature classes at school boring, terribly boring. Something to learn by heart one evening, pass the test, preferably with good marks, and forget on the morrow.

Open the books on page 129, and read the table with various symbols and their meanings in Late Medieval literature. ‘The Thesaurus of Medieval Allegories and Symbols’. Old, dry-as-bone facts, and totally useless. Unicorn stands for virginity, lion for pride, wolf for greed, ebony is for persistence, sword for power and strength and justice and punishment and who cares. Black signifies sin and darkness, white purity, red blood and power and love and yellow is for Judas and all traitors in general.

Greek myths, as explained in the textbooks, were nonsensical, silly old stories written or compiled by men who probably never existed (thanks for this ‘fun fact’ beloved textbook). In the beginning there was Chaos, and somehow it begot Eros and Gaia, whose husband was Uranos who gave birth to the Cyclopes and the Hundred-Handers and the Titans. More names! Demeter, Hades (hey, I know this dark guy from the cartoon), Poseidon (cool trident, a sculpture of this ridiculous fishman stands at our city square), Hera, Zeus… and all his children and love interests. Leto, Maia, Dione, Semele, Mnemosyne. Athena, Hermes, Artemis, Apollo, Dionysus, Heracles… Chaos indeed. But not just primordial. Everlasting.

Now that I’ve read about the characters, I can read about the point of those stories (if any exists). Myth tells a sacred story. Well, those stories I’ve read are either funny or stupid or scary. It explains the beginning of the world, natural phenomena, it shows that the universe exists for a reason. Yes, to contain all that chaos. The heroes of myth are beings with extraordinary powers. OK, extraordinary. And bizzare. Women with snakes in their hair turning people to stone, flying horses, flying dudes carried by wings of feathers and wax… I’ve had enough. And the history book tells me they really believed all of this was true. Well… ‘They were dumber back then’.

Now, some terminology. Myth. Mythology. Cosmogonic myths. Theogonic. Anthropogenic. Etiological. Heroic. Myths can show us important truths about the world. Of course. How to interpret myths… hmm, maybe this section will tell me how to make sense of this… weird mythology thing. Demeter myth explains why the seasons change. Because some made-up guy stole a nonexistent girl? Cool, the ground split open and a black chariot pulled by stallions dark as night rode forth. Because someone plucked the wrong flower. Thank you sir.

Archetypes. Short text on a sidebar. Ancient symbols hidden in the collective unconscious (hey, you should have warned me there will be hard words!). Father, Mother, Old Man, Night, Day. Carl Gustav Jung. Literary topos. Journey, Odyssey, Homer, blind man who may have not lived at all, as the sidebar rushes to explain. Modern myths. Someone compiles a retelling of twoscore ancient myths, and suddenly they become less nonsensical. Now, that’s a fine trick. Homework – draw a tree of the gods and goddesses, heroes, monsters, Hundred-Hands, hellhounds, three-headed dogs… and whatever else appears in those outlandish tales. No, thank you. Let me read Tolkien.

Now, the account of my experiences with mythology is somewhat exaggerated. My personal contact with myths and symbolism was that bad only in the beginning. In my later school years, I took part in some contest for school children, and the topic was mythology. I had to borrow one of those compilations from the library and read it, and it was surprisingly good. But still, those tales were little more than pointless fables to me.

Then I started reading Tolkien, not realising I’m reading myths, but of course I was, just a different kind than I was used to. Now, those were the stories I could fall in love with, and I did. The Silmarillion first, then LOTR and The Hobbit… and all other texts by Professor Tolkien I could get my hands on. The Children of Hurin, borrowed from library as I was returning home on the last school day before my winter break, mere days away from Christmas. That day we had our class Christmas Eve ‘supper’ (in the morning, of course). I remember that day in 2012, December the 21st, the day some said the world would end. I hoped it won’t, I wanted to read about Turin and Beleg, tragic misunderstandings and long-lost sisters, about black meteoric iron talking swords and golden dragons. Then The Unfinished Tales, The Tales from the Perilous Realm, later books about books. A book analysing the deeper meanings and clues hidden in songs and poems of The Hobbit were among first literary analyses I actually liked.

As I grew older, I understood more. Tolkien wanted to create a mythology for England, a Legendarium of stories ranging from historical chronicles, through epics and heroic poems, to romantic ballads, walking songs and Hobbit rhymes. Those stories were rooted in languages, those of our world Tolkien came to love, and those tongues of his own. They were inspired by old Anglo-Saxons histories and songs, by Norse myths of Scandinavia, tales I never heard before, but now liked better than those of the Greeks and the Romans. Nevertheless, I failed to see any myths based on astronomy, or those with symbolic meaning.

Then in 2014, during second holiday month and half of September, I read A Song of Ice and Fire, and thus I found the first tale as captivating as those of Tolkien’s. In October The World of Ice and Fire was published, and further kindled this passion. I joined the Westeros forums, and spent some time bumbling around in there. I had few (to be generous) interesting ideas and theories of my own, my posts seem so silly and generic now that I read them again. But that did not matter, as long as I could read those fascinating essays and theories of other posters. In 2015, LML started his Mythical Astronomy (back then Astronomy of Planetos) project. I read the first essays, understood little, but still enjoyed them. But as weeks and months went on, I digested all of it and discovered the amazing world of symbolism and mythology anew.

The myths are not nonsense, they simply speak to us in a language different from the one we use daily. The language of symbolism. And I saw that symbolism is more than reading long lists of plants, animals and colours, with their symbolic or allegorical meanings explained. Symbolism is an intellectual game, as engaging as any sport, or even more. A way to communicate truths over centuries and millennia, as the languages change and evolve, as peoples and nations rise and fall. Some things are unchanging. The nights are always dark, though today filled with dim electrical lights for those of us who live in cities, which dim out the stars… but its enough to leave them for some time, go to the mountains or visit a more rural area, and the stars are still there, arrayed in their constellations. The sun always rises, and sets. The same stars blaze in the night sky, their apparent movement changing slowly in the great precessional cycle. The same constellations can be observed, though we might give them different names than those who lived thousands of years ago in lands far away. But human nature remains unchanged, and although we have things like electricity, the internet and wield the power of fossil fuels and nuclear fusion we’re still only human, like those who lived thousands of years ago. Although we appear to be looming over them like giants, with our medicine, technology and culture, ultimately, we’re not so different from our ancient hunter-gatherer ancestors. Love, hate, friendship, tears, laughter, wars, disasters, joy, births, deaths. We may have better technology and – theoretically – better understanding of nature. Yet we live on the same planet, under the same sky. There is wisdom to be learned from those ages drifting ever further away. Myths speak to us about human nature, growing up, fatherhood and motherhood, dealing with the loss of our loved ones, making sense of this beautiful but often harsh world… speaking of natural events here on Earth and in the sky, whispering words of wisdom in the language of symbols.

Previously, I cared little about stars, waxing moons, waning moons, full moons, new moons, eclipses and changes in day length. The sky in my city is often hidden, by clouds or smog, and light pollution is so heavy that stars can be seen rarely, and even then, only the brightest. I couldn’t name any constellations, nor see those imaginary shapes in the sky. This January I saw Orion’s Belt for the first time. Alnitak, Alnilam, Mintaka. Mentioned in the Bible and Kalevala. Known to Babylonians, ancient Egyptians, Armenians and Finns, the peoples of Siberia, the Seri people, the Lakota, even in the distant Polynesia. But unknown to me. I don’t claim to be an expert in this field even today, but I’ve read about the basic stars and constellations, their appearances in myths and stories. I know that myths describing those stars exist. One step, and small, but at least forward. Knowing the stars and astronomical phenomena, we can uncode the hidden meaning of some myths. In other cases we’ll need knowledge about historical context, plants of that region, traditions and customs, invasions and migrations, the cycle of seasons, and numerous other things. But now we realise that myths are not pointless, stupid fables. They have purpose, and meaning. We simply have to uncode it. That’s a small price to pay to gain the access to wisdom and lore and knowledge and history of countless generations.

Thanks to LML’s Mythical Astronomy, I saw not only those ancient patterns, but also how some modern artists use that symbolism to weave their own stories. And his essays convinced me George R.R. Martin is one of them.

The ancient fables of the Known World of ASOIAF, from places we get to know in the opening chapters of the first book, and places of which we hear only rumours, are based on actual events. The Long Night is this world’s global myth, while the Great Flood is ours. Azor Ahai and the forging of Lightbringer the Red Sword of Heroes cycle are the monomyth of Westeros and Essos. Astronomy explains those stories, the legends of ice and fire. Just like in our world, the observation of heavens was of crucial importance to the ancients. Few changes in the usually fixed pattern of stars and planets would go unnoticed if you can see the night sky clearly almost every day. And what they saw, they’d attempt to explain and pass down, in the universal language of myth. Sea-dragons might be meteors or comets landing in the sea. Storm deities personify the wrathful forces of nature. Other tales speak of the changing of seasons and climate, of isles sinking in the ocean and new land rising from the depths. And in the world of ice and fire, there surely will be tales explaining the Long Night.

As LML discovered, the Qartheen myth, the story about two moons in the sky, one of which wandered too close to the sun and cracked from the heat, with thousand thousand dragons flying out, so implausible at first glance, might be the key to unlock this world’s greatest secret. Planetos – as many fans call the planet on which Westeros and Essos are located – probably really had two moons, not unlike Arrakis-Dune. The red comet pierced this Second Moon, by accident or guided by malicious, nasty sorcerer. The comet, blazing in the sky like a bleeding star or burning brand, is the Red Sword of Heroes. Or villains. The moon was Nissa Nissa from the forging of Lightbringer story, and the sun was Azor Ahai. And the dragons? Moon-meteors, hitting Planetos on the onset of the Long Night. Rising ash and smoke would blot out the sun, causing the prolonged period of darkness.

***

The Mythical Astronomy of Ice and Fire by LML: A Summary by Archmaester Aemma

I’ll give you a little context and a taste for how this type of analysis works, I’ll briefly summarise LmL’s main thesis. First, a quick refresher on the Qartheen origin of dragons myth. (This is the legend Dany hears from her handmaiden Doreah in A Game of Thrones).

Once there were two moons in the sky, but one wandered too close to the sun and cracked from the heat. A thousand thousand dragons poured forth, and drank the fire of the sun. That is why dragons breathe flame. One day the other moon will kiss the sun too, and then it will crack and the dragons will return.

Now let’s compare with the key “third forging of Lightbringer” from the the Azor Ahai myth:

A hundred days and a hundred nights he labored on the third blade, and as it glowed white-hot in the sacred fires, he summoned his wife. ‘Nissa Nissa,’ he said to her, for that was her name, ‘bare your breast, and know that I love you best of all that is in this world.’ She did this thing, why I cannot say, and Azor Ahai thrust the smoking sword through her living heart. It is said that her cry of anguish and ecstasy left a crack across the face of the moon, but her blood and her soul and her strength and her courage all went into the steel. Such is the tale of the forging of Lightbringer, the Red Sword of Heroes.

Although it may not seem like it at first glance, there is a surprising amount of overlap in these tales. Note how the moon “wanders too close to the sun” and that the Dothraki calls the moon a wife and the sun her husband. Compare this to Azor Ahai calling over his wife, Nissa Nissa – this implies Azor Ahai as the sun and Nissa Nissa, his wife-moon, ‘wanders too close to him’. What then happens in each of these tales? Well Nissa Nissa gets stabbed and her cry leaves ‘a crack across the face of the moon’, and the Qartheen myth implies the moon being destroyed as well. Finally, the moon releases dragons and Nissa Nissa forges flaming sword Lightbringer. And, would ya know it, Xaro Xhoan Daxos calls dragons ‘flaming swords above the world’ – implying that the result of Nissa Nissa’s death and the Qartheen moon destruction myth are symbolically equivalent.

In addition to this, The World of Ice and Fire gives us the myth of the Bloodstone Emperor, a man who killed his sister (like Azor Ahai killing Nissa Nissa because incest is a thing we know royals do in Planetos), and worshipped a black stone that fell from the sky (probably a meteor from the moon destruction of Qartheen myth), a crime so repugnant that the world was cast into darkness. This sounds like the Long Night, potentially caused by an impact winter that resulted from the moon destruction event raining down meteors on earth – implying Azor Ahai as the villain, not the hero. For more on this check out LmL’s Bloodstone Compendium.

***

George R.R. Martin and Tolkien

Thus myth and legend tell us about the cause of the most important ancient event of this world. This is one of the crucial things to understand about ASOIAF. Myths of Westeros, Essos and other lands describe, making use of symbolism, often based on symbolism and mythology of our world, the ancient astronomical and earthly events. But hints can be found in the ‘main story’ as well. Characters such as Daenerys Targaryen, Robb Stark, Jon Snow, Stannis Baratheon and Theon Greyjoy play the archetypal roles established in the age of heroes. Nissa Nissa and Azor Ahai. The Last Hero and the Grey King. Night’s King and his Queen. Events from that time are enacted once more, once symbolically. Thus, by looking at the present we can fill up holes in the histories we know, and by looking at the past, we can predict the future.

I trust most of you are familiar with LML’s great ideas anyway. I’ll be using LML’s ideas and research quote heavily in this essay so, whilst I provided a precis above that should allow you to grasp most of this essay, it may be a little less intuitive for people unfamiliar with LML’s ideas.

With Tolkienic Song of Ice and Fire episode one, I tried to stick with references to Tolkien found in ASOIAF and related material which are easy to see and understand without knowing Mythical Astronomy. Things like references in names, places, descriptions, sigils, historical events and such. This time, we’ll deal with ‘mythical astronomy’ of Tolkien. While I don’t think Tolkien wanted to hide, using symbolism based on astronomy, a second story behind the story he was telling, The Lord of the Rings and his other works are full of such symbolism, and references to various stars and constellations, as many characters and places are symbolically connected with astronomy. Themes such as the duality of sun and the moon, of day and night, of light and darkness, and of ice and fire can be found there as well.

In fact, it seems to me that some parts of George R.R. Martin’s mythical astronomy symbolism were inspired by Tolkien’s usage of this tool. But while Tolkien’s goal was to write a mythology, GRRM wanted to hide his mythology in the background of the fantasy story he was writing. This goes well with what numerous other fans and authors wrote about ASOIAF and its influences. GRRM often incorporates symbolism and traditions from our world’s cultures into his own world. Weirwood trees as Yggdrasil, Kings of Winter and wicker men, Garth Greenhand and sacrificed sacred kings… It is truly amazing how GRRM reconciles all that source material and weaves one consistent story of his own. H.P. Lovecraft, Frank Herbert, Jack Vance, Roger Zelazny… and J.R.R. Tolkien.

In the first chapter of the first episode of this series I explained how, in my opinion many people misunderstood GRRM’s approach to Tolkien. Unlike many authors who just copy-and-paste Tolkien’s ideas, GRRM rethinks those ideas, rejects some he doesn’t agree with, develops or adds others… In his own words:

When I read fantasy books by other writers, particularly Tolkien and some of the other people who followed Tolkien, there’s always this desire in the back of my head to reply to them: “That’s good, but I’d do this part differently,” or, “No, I think you got that wrong.” I’m not specifically criticizing Tolkien here — I don’t want to be portrayed as blasting Tolkien. People are always trying to set up this me-vs.-Tolkien thing, which I find very frustrating because I worship Tolkien, he’s the father of all modern fantasy, and my world would never exist had he not come first! Nevertheless, I am not Tolkien, and I am doing things differently than he did, despite the fact that I think Lord of the Rings was one of the great books of the 20th century. But there is that dialogue that’s going on between me and Tolkien, and between me and some of the other people who follow Tolkien, and it’s a dialogue that’s continuing.

With this episode, I’ll try to show you how Tolkien used symbolism based on astronomy, and how GRRM might have been inspired by it. This means we’ll discuss the cosmology of Arda, the Two Lamps and the Two Trees, the Sun and the Moon, swords like Narsil/Anduril and Gurthang and characters such as Galadriel, Fingon, Feanor, Nerdanel, Feanor’s Seven Sons. We’ll also take a look at an interesting ice and fire split in the House of Finwe, Morningstar and Evenstar related symbolism of Earendil and his sons Elrond and Elros (and their descendants), and of the Numenoreans. I’ll also expand on the connections and parallels I’ve found between the story of the Downfall of Numenor and the Great Empire of the Dawn legend found in The World of Ice and Fire. I only alluded to it in the first essay, as it was already over 20 000 words long, and to fully explore this topic I’d need… well, who knows how much space. And that can be hard to digest, especially for readers not well-versed in the meanders of Tolkien-lore. But I hope that together, we’ll manage to decode some of the hints GRRM has left for us!

This time I’d like to pay more attention to new terms, concepts and characters I’ll be talking about. TolkienicASOIAF Episode I was but an introduction to my series, where we explored some basic references to Tolkien that GRRM is making. Thus, no lengthy analysis of things like symbolism was needed. For example, you could agree that Ser Gladden Wylde is a reference to the Gladden Fields from LOTR, or not. There wasn’t much to discuss. With this piece, it’s going to be different. Well, I can’t wait to show you all those fine samples of Tolkien’s beautiful prose, and point out to the symbolism hidden in there.

We’ll revisit Numenor, and the realms the survivors of its downfall founded in Middle-earth, Arnor in the north and Gondor in the south, paying more attention to Elendil and his sons, Isildur and Anarion, the city of Osgiliath, the palantiri stones, the sword Narsil… and Minas Morgul, once Ithil. We’ll look out for flaming swords, dragons and other fell beasts, corrupted moons, Long Nights and other fun stuff.

There will be some sections where I’ll summarise the most important events of The Silmarillion. While they are not directly relevant to our ASOIAF discussion today, they provide the context for those characters, events and places that are very important. I encourage you to read them, but if you’d rather jump straight into ASOIAF analysis, or are a huge Tolkien familiar with all this lore, feel free to skip them – their headlines are underlined.

***

But before we move on, I’d like to express my gratitude to LML, host of The Mythical Astronomy of Ice and Fire blog and podcast, my dear friend, without whose encouragement Tolkienic Song of Ice and Fire would never come to be. And to all fellow Mythical Astronomers and members of the ASOIAF community on Twitter (Twitteros) and many forums and fansties, authors of many excellent essays, videos and podcasts. Let me name Crowfood’s Daughter of The Dipsuted Lands, Joe Magician of YouTube and The Clanking Dragon, Patrick of I Can’t Possibly Be Wrong All The Time, Archmaester Aemma of Red Mice at Play, Maester Merry of Up From Under Winterfell, Melanie Lot Seven, Sweetsunray of The Mythological Weave of Ice and Fire, Darry Man of Plowman’s Keep, and Ravenous Reader. Their essays and videos and podcasts I wholeheartedly recommend. Thanks to all who took part in Twitter discussions that helped to forge and temper the ideas hereby presented, and for bearing with me, as I spammed your inboxes with messages about obscure details of Tolkien’s masterful worldbuilding.

Thanks to all who read my first essay, and helped to spread the word. Thank You for coming here today!

And finally, my undying gratitude belongs to the two great authors, J.R.R. Tolkien and George R.R. Martin, often so different in their ideas and style, yet so similar in that they both created worlds that countless readers came to love.

***

Part I: The Cosmology of Arda

In this section I’ll discuss how peoples of Middle-earth envisioned the world they lived in, its beginning, structure and history. I’ll also explain who Eru Iluvatar is, talk about the Valar and the Maiar, and ancient history of Arda, with special consideration for events such as the destruction of the Two Lamps and the Two Trees, the Long Night and Darkening of Valinor, and the creation myth of the Sun and the Moon. I’d like to dedicate this chapter to LML, without whose encouragement this essay, and the first one, would most likely never come to be, and if it weren’t for his amazing Mythical Astronomy series, I’d have never noticed – nor deciphered – all this astronomical symbolism. Thank you my friend!

Unreliable Chroniclers, History versus Myth, the Round World and the Flat

Now, one of the most crucial things to understand about Tolkien’s mythos, commonly known as The Legendarium, is that those stories were in the making for decades. J.R.R. Tolkien made constant rewrites and changes. Some were minor, for example changing ‘tomatoes’ for ‘pickles’ in the opening chapter of The Hobbit. (To this day, fans speculate why he did it. Some believe that when Tolkien decided that this tale is set in the same universe as The Silmarillion, he wanted to erase this reference to a New World plant – although such plants – like potatoes – appear in The Lord of the Rings, and it is explained that they were brought to Middle-earth by Numenorean sailors. Others are of different opinion – that Tolkien, a well-known perfectionist – came to the conclusion that in April, when The Unexpected Party takes place, it’d be too early for fresh tomatoes).

But other differences between earlier and later versions of the Legendarium are more drastic and explicit – for example, in the one of the elder accounts of the story of Beren and Luthien, Sauron appears as Tevildo, the Prince of Cats, while in The Silmarillion version, he is one of the evil Maiar serving Morgoth the Dark Lord. Another major change was in the very shape of Arda, the world in which all stories of the Legendarium take place. Although in the earlier versions the world was indeed flat, and the perception the Numenoreans and other peoples had was correct – Arda was one hemisphere surrounded by ‘airs’ where the stars and other celestial bodies resided. That is known as the Flat World version of The Silmarillion.

And there is the Round World version, which Tolkien experimented with in his later writings. Here the account of Flat Arda is a myth of the Numenoreans, and the world was always a round planet. Also, it seems that the term ‘Arda’ was supposed to refer to the Solar System as a whole. The Two Lamps, which we’ll soon discuss, never truly existed, and the Sun and the Moon were not a fruit and a flower of the Two Trees of Valinor, but celestial bodies that have existed for eons, like in our world. In this continuity, nearly all more magical and mythical elements of the setting were explained as myths of the peoples inhabiting Middle-earth. The Silmarillion (meaning, the book we can read) was still an in-universe text, but not perfectly accurate, as is the case in the Flat World version of The Silmarillion, but sometimes erroneous. Fans of many works of fantasy might find this strange, but A Song of Ice and Fire fans probably won’t, as they’re well accustomed to the unreliable narrator.

If you think of The Silmarillion as Tolkienic equivalent of The World of Ice and Fire, than in the Flat World version the narrator is infallible and everything happened just as he describes it, but in the Round World continuity the narrator is more like Maester Yandel. Just Yandel’s Westerosi history gets more fantastic as we go back in time, The Silmarillion is mostly correct when describing events of the Third Age, Second Age is also nearly perfectly remembered, although some details about Numenor and distant continents visited by its sailors were lost when Numenorean archives were lost to the waves, with Elendil and his sons saving a fraction of that knowledge. Meanwhile, some First Age events can be questioned – ancient history of mankind, events where nearly all who took part in them died. But the most ancient histories should be taken with a very big grain of salt, especially those that took place before the Elves woke and met with the Valar.

Even in the Flat World version we are invited to question the oldest Elven legends. Of those Cuivienyarna is the most ancient. It describes how the first of the Elven kind woke on the shores of lake Cuiviénen in the far east of Middle-earth (Cuiviénen wasn’t a true lake, but a bay of the inland Sea of Helcar, in the foothills of the Red Mountains – not of Dorne).

***

The Cuivienyarna

In that tale, the first elves to awake are Imin (First), Tata (Second) and Enel (Third). Then three first elven women awake, Iminyë, Tatië and Enelyë. Their names also come from the words for first, second and third. Imin marries Iminyë, Tata Tatië and so on. The three first elven couples live their little lakeshore dell and begin exploring its surroundings. Not long after they find six sleeping pairs. By the right of his seniority, Imin chooses those 12 newly-awoken elves as his companions. At this point, there are 18 elves. In another valley, they see nine sleeping pairs, and Tata the Second chooses them for his tribe. Now there are 36 elves. A bit further, in a birch grove, they come across twelve pairs, and those 24 become Enel’s companions. Now that there are 60 elves, Imin sees that his tribe is by far the smallest, with only 12 members. When another group, of 18 pairs, is found in a fir-wood, Imin withholds from choice, believing that each group they find will be more numerous, and thus if he chooses the final, his tribe will be the most populous. Thus those 36 become Tata’s companions. Later, the 96 elves find 24 pairs, and Imin lets them join Enel’s tribe. But Imin’s hopes are mocked, and no further sleeping elves are found. According to the legend, all elves come from those 144 awoken elves, 72 fathers and 72 mothers.

This story explains how three main elven tribes came to be – those 14 Minyar (the Firsts), people of Imin and Iminyë’s tribe, became the Vanyar, half of the 56 Tatyar became the Noldor, and about three in five of the 74 Nelyar became the Teleri. In the Flat World continuity this tale might be true, but in the Round World version, the version with less mythical continuity, such histories are almost certainly fairytales. Here Cuivienyarna is not a historical account, but a tale for elven children, so they can learn the basics of the duodecimal counting system used by the elves.

***

Tolkienic Caveat

I’ll have more to say about the various sunderings and tribes of the elves later. I brought up this topic here to better demonstrate how drastic the division between the Round and Flat World continuities are. J.R.R. Tolkien died before The Silmarillion was published, so we don’t know how the final versions of his myths would look like. But for some fans, myself included, all those different accounts really enhance the mythical feel of those stories. After all, in the real world, we often have different and sometimes even conflicting versions of the same myths. The Silmarillion as we know it presents one consistent story, compiled by Tolkien’s son Christopher. But to achieve this consistency some later ideas of Tolkien had to be dropped, or not mentioned, as they weren’t developed enough to decide what the author intended. Many stories were rewritten to fit the Round World continuity, but numerous others were not, and no one knew how Tolkien would have changed them. In the end, The Silmarillion, as published in 1977, is written from the Flat World perspective, and we can read about the other possibilities in the monumental The History of Middle-earth 12-volume series.

In this essay, for the sake of clarity, I’ll mostly stick to the published version of The Silmarillion, as it’s the one most Tolkien readers are familiar with, and which George R.R. Martin has surely read. I mean, we can’t rule out that he’s familiar with all those other versions, but I think that if he were to include references to Tolkien’s stories in his own books, he’d choose the ‘official’ version, the one more people know. Still, when discussing things like cosmology, I’ll mention how they were supposed to look like in other continuities.

With that caveat given, let us delve into the most ancient history of Arda.

***

Valar Morghulis

I imagine every fan of A Song of Ice and Fire is familiar with these words, the creed of the Faceless Men of Braavos. But fewer realise that that both parts of this phrase come from J.R.R. Tolkien’s languages, the first one from Quenya of the High Elves (as I’ve said, we’ll get to those divisions and terms shortly) and the latter comes from Sindarin of the Grey Elves. Minas Morgul is a thing of the Third Age of the Sun, the fortress guarding one of the few entrances to Mordor, and the seat of the Witch-king, Lord of the Nazgul (Ringwraiths). I think every person who has seen the LOTR movies or read the books knows this place, even if he or she doesn’t recognise the name. Minas Tirith’s twin city, the fortress of corpse-pale stone, surrounded by ominous green glow. Gargoyles grimacing where the bridge begins, the polluted stream of river Morgulduin silently flowing below it. The stronghold of Dark Sorcery, its sigil being the corrupted moon and skull. Frodo and Sam crawling past the bridge with Gollum, a beam of green flame suddenly sprouting and piercing the clouds and vapours like one of the poisoned Morgul-blades. The enormous gate opening, and hosts of the Dark Lord under the Witch-king and his cruel lieutenants pouring forth like a dark wave. A dragon-like Fell Beast spreading its wings from the battlements overlooking the bridge and the gate, its shriek dartling the ears of the two Hobbits. An army marching on Minas Tirith. Haunting images indeed.

But morghulis is the latter part of the Braavosi proverb. As I said, Minas Morgul is a thing of the Third Age. I saw it fitting that we shall discuss it in the final part of this episode, for the sake of chronology, but also because that section will rely most heavily on mythical astronomy and speculation. And thus, we begin with the Valar and the beginning of Arda, the centuries before even the First Age – from past so distant and inconceivable, when there was no time, through the Years of the Lamps, then the Years of the Trees, and finally the Long Night (yes, this term, so important in ASOIAF, appears in Tolkien’s writing as well).

The Valar

I said that the myths of The Silmarillion become more and more unreliable as we go back in time. But this isn’t always the case. In both versions of the Legendarium, the most ancient tale – Ainulindalë – is true. Or at the very least, describes real events, the creation of the world by Eru Iluvatar using symbolism. The book published as The Silmarillion contains not only Quenta Silmarillion, The Tale of the Silmarils, but also four shorter texts. Quenta is in the middle, followed by the Akallabêth, which tells of the rise and fall of Numenor in the Second Age, and Of the Rings of Power and the Third Age, which describes the major events which took place after the Downfall of Numenor – the founding of Gondor and Arnor, the return of Sauron and the War of the Ring.

Before the chronicle of the wars of the Noldor and Morgoth over Feanor’s three precious jewels, come two texts. Ainulindalë, the account of the creation of the world by Iluvatar, and Valaquenta, the compilation of elven lore about the might beings known as the Valar, with some consideration for the Maiar and Morgoth’s servants like Sauron and the Balrogs.

Although there were no elven nor humans to witness the creation of Arda, the history described in Ainulindalë is true, in essence if not in details. The full account of the Music of the Ainur (as that’s what this title means in Quenya) that preceded the beginning of time is incomprehensible to humans of Middle-earth, and even the elves turned to symbolism and metaphor to describe the grandiose song that shaped the universe. But unlike our own creation myths, in Tolkien’s world, there can be no doubt that there was indeed Eru Iluvatar the God, who first created the angelic beings known as the Ainur. While the reader can speculate whether the Lord and Ladies of the Valar really literally shaped Arda like a craftsman shapes his works, or if the descriptions of those might beings raising mountain ranges and moving stars and performing many other marvellous acts are what elven chroniclers understood of natural processes overlooked by the Valar, it is certain that Eru Iluvatar and the Valar are real.

***

Ainulindalë

Ainulindalë describes how Eru Iluvatar (The God) created many spiritual beings called the Ainur, which in the language of the High Elves, Quenya, signifies the Holy Ones. In many letters, Tolkien would describe them as angels of his Catholic faith. Each of the Ainur wielded great power, but as the Great Ones tower over other beings, Iluvatar transcended them infinitely, as each Ainu (singular form of ‘Ainur’) could comprehend only that part of Eru’s mind from which he came. (While talking of the Ainur it is hard to determine which pronouns to use, as they are spiritual beings who don’t require physical bodies, but still, they have genders, which affect the physical forms in which they appear to better communicate with humans and elves).

Eru means ‘He Who Is Alone’, while Iluvatar signifies ‘The Father of All’ (Allfather). I’ll describe the principal of the Ainur a bit later, while discussing the Valar and the Maiar, who belong to this group of beings.

The greatest of the Ainur was Melkor, which means ‘he who arises in might’. If you’re familiar with Morningstar and Evenstar based symbolism, and I guess most Mythical Astronomy fans are, then you can probably see where this is going, even if you have never read Tolkien’s books.

Iluvatar gathered all of the Ainur, and presented to them a musical theme, and the Ainur started their famed song, the Music of the Ainur. But because of Melkor, a discord entered this melody, and it was no longer a beautiful tune, but a turbulent sea of sounds. Then Iluvatar gave the Ainur his second theme, but again, Melkor’s discord rose again. As the third theme played, it seemed that there is not one music, but two songs played at once, once deep and beautiful, but full of sorrow, the second loud, but vain and clamorous, and without rhythm. Iluvatar rose, and the music died out, and no such music was heard again anywhere in the universe. According to prophecy, the world will end in the same manner as it has began, with another song, the Second Music, in which elves and humans will take part as well.

After the third theme ended, there came silence, and Iluvatar showed the Ainur a vision, telling them to behold their music. And they saw the history of the world as it unfolded before their eyes, and for the first time, glimpsed the Children of Iluvatar, Men and Elves, which Iluvatar sung personally into the third theme. Then Iluvatar said ‘Eä! Let these things Be!’, and this word, Eä, became the name of the Universe as a whole. And in the darkness of the primordial Void, the Ainur saw light appear, like ‘a living heart of flame’. Eru sent his Flame Imperishable into this created universe, and it became real.

Iluvatar permitted those of the Ainur who willed so to enter this physical world. And in this way, although Ainur beyond count remain with Eru in his Timeless Halls beyond the world, many entered Eä. The mightiest of those where the Valar, the Powers of the World, whom humans often called gods, but in reality, the Fifteen Valar were emissaries of Iluvatar, and guides to his Children. All were true to this mission, with the exception of Melkor, who later lost his Valar status.

There are seven Lords of the Valar, and seven Queens, also knowns as the Valier. They form the Tolkienic ‘pantheon’, as they seem to be heavily inspired by the Greek and Norse gods, but adapted to Tolkien’s Christian perception of the world. They are not truly gods, though some inhabitants of Arda know them by this name, but the true God’s emissaries. I’ll describe the Fourteen of the Valar, not only because I like talking about Tolkien’s works, as you’ve surely noticed, but also because by using the term ‘Valar’ in A Song of Ice and Fire GRRM might be trying to show us that he was inspired by the Powers of Arda while creating pantheons and religions and myths for his fictional universe.

With Melkor no longer a Valar, we will start this description of the Valar by looking at his brother Manwe.

***

Ainulindalë: A Summary by Archmaester Aemma

Here follows a summary of Ainulindalë, the account of the creation of the world, for those of you who chose to skip this section, where I narrated the tale of the Music of the Ainur.

The Ainulindalë describes how Eru Iluvatar (The God) created many spiritual beings called the Ainur, which in the language of the High Elves, Quenya, signifies the Holy Ones. In many letters, Tolkien would describe them as angels of his Catholic faith. In Quenya, Eru means ‘He Who Is Alone’, while Iluvatar signifies ‘The Father of All’ (Allfather). Iluvatar gathered all of the Ainur, and presented to them a musical theme, and the Ainur started their famed song, the Music of the Ainur. The greatest of the Ainur was Melkor, which means ‘he who arises in might’, and he introduced a discord to this melody, so that it was no longer a beautiful tune, but a turbulent sea of sounds. This happened a second and a third time, with the Ainur creating beautiful music and Melkor introducing disharmony. After silence that followed the third song, Eru Iluvatar used this music to create the universe, Eä, and permitted those of the Ainur who willed so to enter this physical world. And in this way, although Ainur beyond count remain with Eru in his Timeless Halls beyond the world, many entered Eä. The mightiest of those where the Valar, the Powers of the World, whom humans often called gods, but in reality, the Fifteen Valar were emissaries of Iluvatar, and guides to his Children (Elves and Men). All were true to this mission, with the exception of Melkor, who later lost his Valar status and became known as Morgoth, the Dark Tyrant.

***

Lords and Queens of the Valar

* Manwë, also known as Súlimo (Breather), has many titles: High King of Arda, Lord of the Breath of Arda, Elder King and Vice-regent of Eru. His sceptre is made of sapphire, his robes are blue, and ‘blue is the fire of his eyes’, as The Silmarillion tells us. Manwe’s ‘area of expertise’ is wind, from the most faint whiffs in the meadow to the winds blowing in the Veil of Arda, the upper atmosphere. One of his closest friends was Ulmo, the Valar ruling all waters, and together they created clouds. As I’ll show in a later section about Numenor, Manwe shares some similarities with the Storm God of the Ironborn religion, which is not surprising, as both are sky deities. But it’s possible that this is not merely an accidental similarity, and I think some of the language used to describe the foe of Iron Islanders suggests that GRRM made an intentional parallel here.

For those of you who are not familiar with this character, I think the easiest way to imagine him is to think of all the ‘sky-father’/’storm god’ mythological figures, but also of Archangel Michael of Christian faith. (In fact, the Valar can very well be thought of as Archangels, and the rest of the Ainur as angels).

Manwe’s seat is Ilmarin, the tallest of the towers built on the highest peak of all Arda, Taniquetil the White Mountain, Amon Uilos, Oiolossë the Everwhite, Elerrína Crowned with Stars. If his wife Varda sits beside him, Manwe can see all that happens across the world, his sight piercing mist and darkness alike, and she could hear all. The Great Eagles are Manwe’s servants.

* Manwe’s wife Varda was given many titles and epithets by the elves, just like her husband. Those who spoke Quenya of the High Elves called her Elentári, Queen of the Stars, and Tintallë, the Kindler. For the Grey Elves, she was Elbereth, The Star-queen, Gilthoniel the Strakindler and Fanuilos the Everwhite. In the beginning, Melkor who would become the Dark Lord desired light, but could not control it. He turned to Varda, but she rejected him, and thus Melkor hated her and feared her more than any other of the Valar. It was Varda who filled the Two Lamps with light, and made many of the stars of Arda, arranging them into constellations.

* Ulmo is the Lord of Waters, Dweller in the Deep and King of the Sea. Normally I’d ask you to imagine him as a Poseidon-like figure, but since we’re talking ASOIAF there is no such need, for the Drowned God is also remarkably similar. The Valaquenta describes him in those words: Arising of the King of the Sea was terrible, as a mounting wave that strides to the land, with dark helm foam-crested and raiment of mail shimmering from silver down into shadows of green. Nevertheless, Ulmo loves the Children of Iluvatar and never forsook them. As you might remember, in LOTR the Nazgul are afraid of water, and some fans speculate that this is because they fear the Lord of Waters, not only seas and oceans, but also the smallest stream. Among Ulmo’s attributes are the Ulumúri, the great horns of the sea made of white shells. It is said that when one hears them, longing for the sea will awake in his heart. But the true voice of Ulmo is the tongue of the waves: Ulmo speaks to those who dwell in Middle-earth with voices that are heard only as the music of water. For all seas, lakes, rivers, fountains and springs are in his government; so that the Elves say that the spirit of Ulmo runs in all the veins of the world. This description reminds me of that scene in A Feast for Crows where Aeron mentions that his Drowned God speaks to his faithful in the language of the leviathan and in the waves hammering on the shore.

One of the most well-known depictions of this Vala is the scene where King of the Sea appears before Turin’s cousin Tuor and bids him to go and find the Hidden City of Gondolin. Its author is Ted Nasmith, who illustrated parts of The World of Ice and Fire as well. It’s curious that GRRM chose this artist famous for his works related to Tolkien’s Legendarium, don’t you think? Ted Nasmith was also the illustrator of his 2011 ASOIAF calendar, so I think this speaks of deep admiration GRRM has for his works. And I suggest this admiration comes from the time when George enjoyed his Tolkienic graphics in The Silmarillion.

* Aulë is the Smith of the Valar, the master craftsman and expert in all matters connected with gemstones, jewels, metallurgy, forging and rocks. He desired to create a sentient race, who would be his children. And so he did, creating the first seven dwarves. But nothing can remain hidden from Iluvatar, and Eru spoke to Aulë, pointing out that his ‘children’ are merely mindless puppets, who do only what Aulë tells them to do. The Vala repented and lifted his hammer to destroy the dwarves, but Iluvatar told him to stop. Then Aulë realised that the dwarves showed fear and flinched, although he gave them no such command. It was Iluvatar who took pity and gave them sentience and granted them true life, which the Valar could not do. This the dwarves became ‘adopted’ Children of Iluvatar.

* Yavanna, Giver of Fruits, was Aulë’s wife. She was also called Kementári, which means Queen of Earth. She took care of all things growing, from moss to giant trees, and made them bloom and rippen when harvest-time came. The Valaquenta describes some of her many forms: In the form of a woman she is tall, and robed in green; but at times she takes other shapes. Some there are who have seen her standing like a tree under heaven, crowned with the Sun; and from all its branches there spilled a golden dew upon the barren earth, and it grew green with corn; but the roots of the tree were in the waters of Ulmo, and the winds of Manwë spoke in its leaves. When she heard of the Dwarves, she was afraid that they would fell all the woods of Arda to feed their furnaces and forges. In response to her prayer, Iluvatar sent spirits that became the Shepherds of the Trees, better known as the Ents. How Tolkien’s ideas connected with trees influenced GRRM is a fascinating topic, explored – among others – by JoeMagician in his essay Weirwoods: The Wight Trees.

* Mandos is the keeper of the Houses of the Dead, the Judge and Doomsman of the Valar. His true name is Námo, but few used that name, calling him Mandos after the Halls of Mandos which were his seat. When Melkor was captured by the Valar, he was placed in Mandos’ custody. But generally, Mandos is more similar to those psychopomp figures from mythology who are not evil or malicious.

* His wife is Vairë, the Weaver, whose tapestries chronicle all history of Arda.

* Irmo, also known as Lórien, is Mandos’ younger brother. Together they are called the Fëanturi, Masters of the Spirits. But while his brother is responsible for summoning the spirits of the dead to his halls – so Elves can be re-embodied and return, and Men prepare for their journey beyond the world to Iluvatar – Irmo’s domain are visions and dreams.

* Estë the Gentle is the healer of weariness and hurts. She wears grey, and her greatest gift is rest. Even other Valar visit her gardens to repose from their burdens of ruling Arda.

* Nienna is the sister of the Fëanturi brothers. She is well acquainted with grief and sorrow, and she mourns all wounds the world suffered because of Melkor. But she teaches strength and endurance as well, and those willing to learn from her gain new courage. Among her students was Olórin, who would become Gandalf. Similarly to him, Nienna wore a grey hood.

* Tulkas the Strong was the last of the Valar to enter Arda, but his help in wars with Melkor was great. He needs no weapon, only his fists, but even as he fights, Tulkas is always laughing. This Vala reminds me Lyonel Baratheon the Laughing Storm… or of King Robert, as it is noted that Tulkas isn’t the best counsellor, but can be relied on as fierce warrior and hardy friend.

* Nessa, called the Dancer and the Swift, was his wife. She is swift as an arrow, and deers of the woods are her companions. Still, she can outrun them.

* Oromë the Hornblower is Nessa’s brother. This Vala was known as The Huntsman of the Valar, Great Rider, Aldaron and Tauron, Lord of the Forests. Where Tulkas is cheerful even in battle, Oromë is dreadful in anger. His delight is hunting monsters and other dark creatures, and riding on Nahar, his great horse. His horn is Valaróma the sound of which is like the upgoing of the Sun in scarlet, or the sheer lightning cleaving the clouds. In the elder days he would ride across Middle-earth’s woods, and shadows would flee before him. It was Oromë who first came across awakened elves.

* His wife is Vána the Ever-young, Yavanna’s younger sister who took care of animals and plants both.

As a fun fact, I’ll mention that in older versions of Tolkien’s Legendarium, the Valar had children, known as the Valarindi. And there are the so-called ‘Lost Valar’, characters Tolkien abandoned – Nielíqui (daughter of Oromë and Vána), Telimektar (Tulkas’ son), Ómar (who knew all languages), the warrior Makar and his sister, the spear-wielding Meássë, also known as Rávi (ravennë means lioness). (Shout out to Ravenous Reader!)

Melkor who betrayed Eru and fought other Valar is no longer counted among them. He became known as Morgoth, the Dark Tyrant, and the Dark Lord.

***

The Maiar

Besides the Valar, less mighty Ainur spirits entered Arda. Those became known as the Maiar. Some helped the Valar in their efforts, while others joined Melkor.

The principal of the Maiar were Eönwë, Manwe’s herald and commander of his armies, and Varda’s handmaiden Ilmarë. The Balrogs were Maiar associated with fire who became corrupted by the Dark Lord. Their lord was Gothmog, Melkor’s High-captain.

In memory of this Balrog (or in mockery), a member of Sauron’s army in the Third Age bore this name as well. That Gothmog was a Lieutenant of Minas Morgul who was second in command during the Siege of Minas Tirith. Sometimes, Sauron is like the First Order from new Star Wars movies. The second Dark Lord, a Morgoth wannabe, who just names stuff after First Age artifacts (for example, the battering ram that broke the gate of Minas Tirith was named after Morgoth’s warhammer).

Other important Maiar were Arien and Tilion, who guided the Sun and the Moon respectively (I’ll have much more to say about them when we reach a section about the tale of the creation of the sun and the moon). The group known to the people as the Wizards were all Maiar as well, sent by the Valar to undermine Sauron’s influence: Alatar and Pallando (the Blue Wizards), Curumo (Saruman), Aiwendil (Radagast) and Olórin (Gandalf). Sauron, once called Mairon, which means the admirable, was a Maiar as well. In the beginning he served Aulë the Smith, but later joined Melkor. Melian, who later married the elven king Thingol and gave birth to Luthien was of the Maiar as well.

The final named Maiar were Ulmo’s vassals – Salmar who made his conches and Ossë who rules the coasts and isles of the Middle-earth. He joined Melkor, but later repented thanks to the efforts of his wife Uinen, and was pardoned by the Valar. Uinen is the Lady of the Sea, and to her all sailors cry for protection.

***

The Valar and the Seven

Now, it is possible that some of the Ainur influenced the deities GRRM created for his world – the Storm God has much in common with Manwe, Ulmo with the Drowned God, and Uinen with the Lady of the Waves worshipped by the people of the Three Sisters, to name a few. But recently, I began to wonder whether the Faith of the Seven itself might have been inspired by the Valar. Of course, it is largely based on Catholicism and the Holy Trinity, but the Valar might have played a role as well. There were seven Lords of the Valar, and seven Queens after all.

And there are some similarities between the Seven and the Aratar (The High Ones of Arda, The Exalted Ones), a group of the Eight greatest Valar. I’m not entirely convinced about this theory, but still, some similarities are there. The Aratar are: Manwe, Varda, Ulmo, Yavanna, Aule, Mandos, Nienna and Orome.

If I were to match each of them with one of the Seven, the list would look like this: Manwe-Father, Varda-Mother, Orome-Warrior, Aule-Smith, Nienna-Crone, Yavanna-Maiden and Mandos-Stranger. Ulmo would be left out, but it’s possible that GRRM left him out because he has already used him to create the Drowned God… and there’s this weird story in The World of Ice and Fire where one of the Hoare kings of the Iron Islands decrees that the Drowned God is one of the ‘Eight Gods’. This might be a reference to the Aratar. Now, the matches for Manwe, Aule, Mandos and Nienna fit nicely, but I’m not so sure about the others. Yavanna might be considered a Mother, as in ‘Mother-Nature’, but also a maiden, as in ‘Corn-maiden’. The Maiden of the Faith ‘dances through the sky’ according to The Song of the Seven, so maybe we should connect her with Varda. Although Tulkas is the ‘main’ warrior of the Valar, Orome’s area of expertise is also martial – riding, hunting and slaying monsters, so I associated him with the Warrior.

As I’ve said, I’m not entirely convinced about those correlations. But it is surely no coincidence that GRRM picked the word ‘Valar’, so they probably were among his inspirations. As Archmaester Aemma pointed out, GRRM might be referencing the Valar, and to be more specific – Mandos – when he has the Kindly Man ask Arya ‘And are you a god, to decide who should live and who should die?’. Valar morghulis…

***

The Two Lamps of the Valar and the Spring of Arda

With this basic introduction to the Valar completed, we can move on to the real main topic of this section, the cosmology of Arda.

According to The Silmarillion, when the Valar completed their task of shaping and decorating Arda, they settled on the Isle of Almaren in the middle of the Great Lake in the middle of the entire world – back then, Arda was perfectly symmetrical. Melkor was gone, or so it seemed, as he fled in the aftermath of the First War, when Tulkas the Valiant descended to Arda. Melkor descended to Arda like the other Valar – in power and majesty greater than any other of the Valar, as a mountain that wades in the sea and has its head above the clouds and is clad in ice and crowned with smoke and fire; and the light of the eyes of Melkor was like a flame that withers with heat and pierces with a deadly cold. But when the others built, Melkor destroyed and corrupted. The Valar battled him, but could not overcome him, until Tulkas joined them in their efforts. Then Melkor passed the Walls of Night that surrounded the world and hid in the void.

The world was at peace, but darkness covered it. To bring light, so plants of Yavanna can flourish, the Valar constructed the Two Lamps. Aule raised the high pillars upon which they were placed, sky-blue Illuin in the north, and golden Ormal in the south. Varda filled them with light, and Arda became covered in trees, grasses and moss. A long period of happiness called the Spring of Arda began.

Arda during the Years of the Lamps, chart by BT

But unbeknownst to the Valar, Melkor returned from beyond the Walls of Night, and settled in the northern region of Arda, where the raised his stronghold called Utumno. From this fortress his hosts assailed the Two Lamps, and destroyed them. The lands were shattered upon their fall, and their flame poured over the earth. Seas rushed inlands, and the primordial symmetry the Valar have designed was lost. The world was once again enshrouded in darkness.

The collapse of the towers changes the layout of all lands, seas and mountains. The Sea of Ringil formed where Ormal once stood, and the Sea of Helcar where Illuin fell. In older versions of this myth, Tolkien wrote that the Lamps were made of ice and Melkor and his Balrogs were able to melt them. In yet another version, Melkor feigned friendship with the Valar and provided them with material from which they constructed the Lamps – ice.

In this era there were three continents that we know of. The Land of the Sun was located in the far east, with its mountain range being the Walls of the Sun. In some texts this continent is called Oronto, The East (Uttermost East), and the highest peak of the Walls of the Sun is called Kalormë, The Crest over Which Sun Rises.

Arda during the Years of the Trees, chart by BT

In the middle was Endor, or Middle-earth, with its Blue, Grey, Yellow and Red Mountains, and the Iron Mountains which protected Melkor’s stronghold of Utumno in the frozen north.

The Great Sea, Balegaer, separated Middle-earth from the Uttermost West. It was there the Valar settled after abandoning ruined Almaren. This continent became known as Aman, the Blessed Realm. The Valar raised the range of Pelóri, the Mountains of Defence, on the eastern shore. There they founded the realm of Valinor, fabled in history and songs.

Now, it is important to note that Aman and Valinor are not synonymous, as apart from Valinor surrounded by the Mountains of Defence, this continent had several other realms. In the south, there was a coastal strip of land between the Mountains and the sea called Avathar, a place of eternal darkness which will play an important role shortly before the Long Night. In the north, beyond Pelóri, lay the land of Araman, a frozen waste connected to Middle-earth by the frozen icy waste shrouded in mists called Helcaraxë, the Grinding Ice or the Narrow Ice.

***

The Two Trees of Valinor

Of the marvels of Valinor much can be said, and here I’ll merely mention the most important areas and places. In the south there were the Pastures of Yavanna, vast sprawling fields ornamented with golden wheat. In the Woods of Oromë animals and beasts of all kind were numerous, and the Vala enjoyed riding and hunting in this grand forest. In the west of the Uttermost West Nienna lived in her Halls, with windows looking outward of Walls of the World. To the Halls of Mandos the spirits of the dead were summoned, immortal Elves to await to be re-embodied, and mortal Men in preparation for their final journey out of this world. Vairë wove the threads of time and decorated the falls of Mandos with tapestries which chronicled the history of Arda. To the Gardens of Lórien all who were weary could come to rest, as their keeper Irmo was the Vala of dreams and visions. Apart from Irmo, Estë the Healer dwelt in the gardens as well. Aulë’s mansions were filled with forges and furnaces.

The place where the Valar gathered to convene was called Máhanaxar the Ring of Doom. Varda and Manwë lived in Ilmarin, atop the highest peak of both Aman and Arda, Taniquetil.

When the Elves came to Valinor, they built many cities and towers. Tirion upon Túna, the seat of the King of the Noldor. Fëanor’s stronghold of Formenos in the north, to which he was exiled for threatening his brother with a sword. Valmar of Many Bells, where some of the Vanyar elves lived, although others dwelt on Taniquetil – one of those was Ingwë, the King of the Vanyar, and High King of the Elves.

The Valar left only one pass in the Mountains of Defense, Calacirya, the Cleft of Light, so people of Valinor could travel to Alqualondë the Swanhaven, seat of the Falmari elves, the people of the waves.

But of all wonders of Valinor, the Two Trees were the greatest. To bring light to the world shattered in the aftermath of the fall of the Two Lamps, Yavanna planted silver Telperion and golden Laurelin on the green mound of Ezellohar, or Corollairë.

The Valar knew that the firstborn Children of Iluvatar will awake shortly, but where they could not tell, and they were afraid that if they were to reshape Arda in similar manner as they once had, the Children might be hurt. This is the tragedy of the Valar – they rarely could use their full power and might to combat Melkor, and later Sauron, as that could harm the Elves, and especially the vulnerable mortal Men. And because Melkor took part both in the Song of the Ainur and the shaping of Arda, his evil influence can’t be truly banished without destroying the world. The tenth volume of The History of Middle-earth is entitled Morgoth’s Ring in reference to this. Sauron bound the Three Rings and all great deeds achieved with their use to his will and fate by forging the Great Ring… but Melkor, who was the greatest of the Valar, marred the very fabric of Arda in its most ancient past.

In the Third Age, the Valar could have attacked Sauron directly, and easily defeat him. But in such war, the entire Middle-earth or its large parts could be destroyed. After the War of Wrath, the final confrontation with Morgoth, the entire realm of Beleriand was shattered and sank. That’s why the Valar elected to send five Maiar emissaries instead of an army, Aiwendil, Curumo, Alatar, Pallando and Olorin. The people of Middle-earth called them Istari, Wizards. They were forbidden to use their full power, and from using fear or force to influence Men and Elves. They were to assist and encourage, but avoid domination, as the will to dominate and forge order with force was what lead to Sauron’s fall in the first place.

But that concerns the Third Age, and we have still the Years of the Trees, the Long Night and two ages ahead of us.

***

The Stars and Constellations of Arda

The Valar felt that the firstborn Children of Iluvatar, known as the Elves, would awake shortly, but the exact time was not revealed to them. And neither was the place. The Valar saw that while Valinor enjoys light, the Middle-earth is largely dark. As Quenta Silmarillion tells us:

Then Varda went forth from the council, and she looked out from the height of Taniquetil, and beheld the darkness of Middle-earth beneath the innumerable stars, faint and far. Then she began a great labour, greatest of all the works of the Valar since their coming into Arda. She took the silver dews from the vats of Telperion, and therewith she made new stars and brighter against the coming of the Firstborn; wherefore she whose name out of the deeps of time and the labours of Eä was Tintallë, the Kindler, was called after by the Elves Elentári, Queen of the Stars. Carnil and Luinil, Nénar and Lumbar, Alcarinquë and Elemmírë she wrought in that time, and many other of the ancient stars she gathered together and set as signs in the heavens of Arda: Wilwarin, Telumendil, Soronúmë, and Anarríma; and Menelmacar with his shining belt, that forebodes the Last Battle that shall be at the end of days. And high in the north as a challenge to Melkor she set the crown of seven mighty stars to swing, Valacirca, the Sickle of the Valar and sign of doom.

The text then goes on to explain that when ‘first Menelmacar strode up the sky and the blue fire of Helluin flickered in the mists above the world […] the Children of Earth awoke, the Ilúvatar’ on the shores of lake Cuiviénen, which was truly a bay of the Sea of Helcar, in the foothills of the Red Mountains, or Orocarni. And thus the first sight their eyes beheld were the stars of Varda. For this reason since the day they have learned who made the stars and constellations, they revered Varda, the Queen of Stars, more than any other Valar. Even in the Third Age they would sing of Elbereth, as many poems found in the Lord of the Rings demonstrate. The Silmarillion then explains that now the world is changed, and those seas and mountains were broken and remade, and ‘to Cuiviénen there is no returning’. But the first of the Elves lived there, and just as the stars were the first thing the saw, the water flowing and falling over stone was the first sound their ears heard.

Now, I will talk about the elves and their tribes, so you understand who the Noldor, the Grey Elves, Green Elves and others were. But before we move on to that, I’d like to pause to talk about those stars and constellations The Silmarillion mentions.

***

This chart shows how the ancient peoples of Middle-earth perceived the world they lived in. In the Flat World continuity the world was really like this, but in the Round World version it was just how people imagined it. Some readers consider the Round World version to be ‘canonical’, because it was the one Tolkien developed in his later writings, although there is no complete book of myths adjusted to this conception. It is worth to mention that it seems that the name ‘Arda’ sometimes refers to the entire Solar System, while ‘Ambar’ refers to Earth alone.

Arda and the Airs in the Flat World version of The Silmarillion, chart by BT

Aman is located in the west of Ambar, and Land of the Syn in the east, with Middle-earth in the middle (surprise). The Earth is surrounded by ‘airs’, which can be understood as layers of the atmosphere. Aiwenórë is the air which living beings can breathe, and its name can be translated as Bird-land, as those animals can fly across it. Above Aiwenórë was Fanyamar, Cloudhome. Together with Bird-air, Cloudhome forms Vista, the atmosphere. Above Vista is Ilmen, where the stars are and flesh can not survive. Menel is the firmament or vault of heavens. Above Menel is Vaia (also called Ekkaia), the Encircling Sea, a dark ocean surrounding the entire world. Vaia is globed by Ilurambar, the Walls of the World, or Walls of Night, which have only two heavily guarded gates – the Door of Night in the west, and the Gates of the Morning in the east. Beyond Ilurambar lies The Outer Void, Avakúma.

Just like George R.R. Martin does, Tolkien describes the constellations and stars in some detail. Westerosi know seven ‘Wanderers’, which appear to be planets of the Solar System, those known to the ancient Greeks. (The word planet comes from ‘wanderer’). We know several constellations as well – Moonmaid, Shadowcat, Sow, Stallion-Horned Lord, Sword of the Morning, Crone’s Lantern, Ghost, Galley, King’s Crown and the Ice Dragon.

Some fans attempted to match those constellations with our own. Even if Westeros’ astronomy is different from ours, it seems that at least some stars were inspired by those visible from Earth – in Visenya Draconic LML speculates that the Ice Dragon is Draco, and the bright blue star that forms his eye is Alpha Draconis, spiced with some Vega symbolism, and in the sixth episode of The Bloodstone Compendium, he identifies the Sword of the Morning as Orion, but with some influence of Venus, the Morningstar and the Evenstar.

Tolkien’s constellations are most likely the same as our own, as Arda is supposed to be Earth in ancient past (at least in some versions of the mythos). But just like for the Westerosi, peoples of Middle-earth often called planets ‘stars’. Here I’ll present the most widely accepted matches for Arda’s stars, planets and constellations:

- Carnil – describes as a ‘red star’ – Mars

- Alcarinquë the Glorious – most likely Jupiter

- Elemmírë the ‘star-jewel’ – Mercury

- Luinil the blue shining star – probably Uranus (other possibilities: Rigel, Regulus)

- Lumbar – Saturn

- Nénar – most likely Neptune

- The Star of Eärendil – Venus (I’ll discuss its history and symbolism later, as according to The Silmarillion, it was created later than the others)

- Borgil – a bright red star, a ‘red jewel’, which according to LOTR is close to the Swordsman of the Sky (Orion) – in this case Borgil would be most likely Aldebaran

In his linguistic writings, Tolkien names several other stars, but those are the most important ones, which appear in the narrative of the books.

Now, the constellations. Wilwarin the Butterfly is Cassiopeia (according to The Silmarillion‘s Index of Names). Sadly, we are unable to identify Telumendil, the Lover of Heavens. Soronúmë, the Eagle of the West, is most likely Aquila. Anarríma the Sun-border might be Corona Borealis (Tolkien Gateway suggests that it might be the Great Square of Pegasus).

***

Orion: The Swordsman of the Sky

Menelmacar the Swordsman of the Sky is Orion (this is confirmed by The Silmarillion index). The Grey Elves called it Menelvagor, and under this name it is mentioned in The Lord of the Rings:

The Elves sat on the grass and spoke together in soft voices; they seemed to take no further notice of the hobbits. Frodo and his companions wrapped themselves in cloaks and blankets, and drowsiness stole over them. The night grew on, and the lights in the valley went out. Pippin fell asleep, pillowed on a green hillock.

Away high in the East swung Remmirath, the Netted Stars, and slowly above the mists red Borgil rose, glowing like a jewel of fire. Then by some shift of airs all the mist was drawn away like a veil, and there leaned up, as he climbed over the rim of the world, the Swordsman of the Sky, Menelvagor with his shining belt. The Elves all burst into song. Suddenly under the trees a fire sprang up with a red light.

In one stage of the development of his mythos, Tolkien considered Menelmacar the celestial image of the great Edain hero of the First Age, Turin called the Blacksword. The Silmarillion never mentions this, but still gives us hints, saying that ‘Menelmacar with his shining belt forebodes the Last Battle that shall be at the end of days’. This Last Battle is Dagor Dagorath, the Battle of Battles, Arda’s Ragnarok or Apocalypse, when Morgoth will return and once again lead his hosts against the Valar, but will be slain by Turin Turambar come again. According to Mandos’ prophecy, Hurin’s son will pierce the Dark Lord’s heart with his famed sword Gurthang, which Eol the Dark Elf made from ‘the heart of a fallen star’, a black iron meteorite. Initially it was called Anglachel and had its twin in Anguirel, which was later stolen by Eol by his son Maeglin, the traitor who revealed the location of the Hidden City of Gondolin to Morgoth. With this sword, Turin accidentally slew his friend Beleg, Glaurung the golden dragon and a certain Brandir the Lame. Gurthang is described in this way: ‘though ever black its edges shone with pale fire’. Dark Lightbringer? (LML suggests that Lightbringer the literal sword might have been a black sword, possibly forged from one of the fallen black moon meteors).

That’s interesting, since in ASOIAF we have Azor Ahai, and as LML suggests, his sword Lightbringer might have been black. This fits with the duality we see in House Dayne, where we get the Swords of the Morning and the Swords of the Evening. This is of course based on Venus, which is both Evenstar and Morningstar, and plays an important role in many mythologies. But GRRM’s Sword of the Morning/Evening might be based on Orion as well, and maybe on Tolkien’s version of this constellation as well… Turin the Blacksword is one of the most morally complex characters in the Legendarium, rivaling maybe Feanor, so I could see why GRRM would make references to him. (Barthogan Stark, called Barth the Blacksword might be another nod to Turin).

It is worth to mention that in order to fight in the Last Battle, Turin would have to be reborn and raise from his tomb under the Stone of the Hapless (no doubt named by Dolorous Edd). After the War of Wrath, when the Valar defeated Morgoth at the end of the First Age, the entire realm of Beleriand in Middle-earth where most of The Silmarillion takes place was drowned by the Great Sea. But the Stone remained above water, as a tiny island called Tol Morwen. And Azor Ahai shall be reborn from the sea…

***

The Stars and Constellations of Arda Continued

In the LOTR passage I’ve just quoted, we were introduced to another constellation, Remmirath the Netted Stars, known to us as the Pleiades. Then there are the seven stars forming Durin’s Crown, which the first dwarf saw over the crystal clear lake called Mirrormere when the world was still young. It became an important symbol for the Dwarves of Khazad-dûm (Moria), who ornamented the Doors of Durin, their eastern gate, with its likeness.

The final constellation of Arda that we know of is Valacrica, the Sickle of the Valar. In The Hobbit Bilbo calls it the Wain, and its other name was Burning Briar. To us it is Ursa Major, the Great Bear.

Although I’m not sure if GRRM was directly inspired by what Tolkien has done when he decided to base his fantasy constellations on those from real-world astronomy (and giving them new names and mythical backstories), the fact that both authors have thought about constellations alone shows the attention to detail and the depth of their world-building.

Now, the most important ‘star’ of Tolkien’s Legendarium is no doubt the Star of Earendil, Venus. But we will discuss it later, as according to the mythos, it was put on the firmament by Varda at the end of the First Age, and its symbolism appears very often in the Second Age and the Third. But the Sun and the Moon deserve out equal attention, as I believe that some myths found in ASOIAF were directly influenced by their creation story found in The Silmarillion. While the Swordsman of the Sky/Orion’s correlation with the pyramids of Giza! – I’m kidding of course – I mean Turin is a bit obscure, this Sun and Moon story is right there in The Silmarillion, which GRRM has surely read – ASOIAF contains many references to this book.

I listed some of those in the first episode, but quick recap might come in handy. We have names like Daeron/Dareon, Beren and Berena. One of the rumours that emerge after the Purple Wedding seems to be a reference to Tolkien – The northern girl. Winterfell’s daughter. We heard she killed the king with a spell, and afterward changed into a wolf with big leather wings like a bat, and flew out a tower window.’ Luthien skinchanged into a bat, and Beren into a wolf when they were about to infiltrate Morgoth’s fortress of Angband. We have Lady Meliana of Mole’s Town, a likely reference to Queen Melian of Doriath, the only of the Maiar who married and elf, and gave birth to Luthien.

Marillion the singer might be named after Tolkien’s book. We have ship-burnings of King Brandon Stark and Nymeria, possibly based on Feanor’s famous burning of the swanships stolen in Valinor. And we have Maedhros and Jaime, both obsessed with oaths… who both were captured and lost their swordhands.

***

Morningstar before Earendil?